Dear Mr. Grant,

I think people reading this letter will wonder how it came to be that I am writing to Ulysses S Grant. You may have similar questions.

The short, most concise answer is because of a book. Let me explain. It all began about two years ago. It was when I realized that I had not ever read an autobiography of a US president. It was a somewhat surprising revelation because my favorite genre of books is biography.

So I did research on a good autobiography of a US president. Up to the present, there have been a total of 45 US presidents, and about 20 of them have written an autobiography, at least for some part of their life. I quickly learned that your memoirs are considered by literary critics and historians to be the very best. I also understand that it is quite common for US presidents in the 20th and 21st centuries who become interested in writing their memoirs - and most of them are interested – to invariably read yours because of the renown acclaim it has earned.

As I read your memoirs, it felt like I was right there on the Civil War battlefields with you. Your writing was so lucid, and surprisingly humorous, that I was disappointed when it stopped so abruptly at the end of the Civil War. I yearned for more about the rest of your life. I thought surely your time as US President must have had a fascinating story or two. Mostly, though, I wanted to know you better.

So I found a biography which encompassed your entire life. It was written by an author who just so happened to have written one of my all-time favorite books – a great biography of Abraham Lincoln. The author's name is Ronald C White, and his book is entitled American Ulysses: A Life of Ulysses S Grant. The book gave me a broader perspective of your life after the Civil War – the immediate aftermath of Lincoln's assassination and your national service, your strained relationship with Lincoln's successor, reconstruction, your 8 years as US President, international traveler, and lastly, the writing of your memoirs and your friendship with Mark Twain.

One new depiction I gained from both books was your life out on the West Coast, specifically San Francisco and then the Pacific Northwest of Oregon and Washington. I myself have lived in the West, both California and the Pacific Northwest, for 36 years of my life so far. And a small city outside of San Francisco is where I presently call home. I was touched that you had shared with your dear wife Julia that after the Civil War, you hoped to move out to the West Coast and settle down here. Alas, that dream did not pan out.

But let me get to the main point of my letter. After reading your memoirs two years ago, and then Mr. White's biography of you last year, I have come to the following unyielding conviction: your generation was right when they believed the three greatest Americans were Washington, Lincoln, and Grant. George Washington. Abraham Lincoln. And you, Ulysses S Grant. This was a common adage in your day. Alas, my generation has forgotten its history.

As another US president named Theodore Roosevelt said at the dawn of the 20th Century: "Yet as the generations slip away... mightiest among the mighty dead loom the three great figures of Washington, Lincoln, and Grant... these three greatest men have taken their place among the great men of all nations, the great men of all time. They stood supreme in the two great crises of our history, on the two great occasions when we stood in the van of all humanity and struck the most effective blows that have ever been struck for the cause of human freedom under the law".

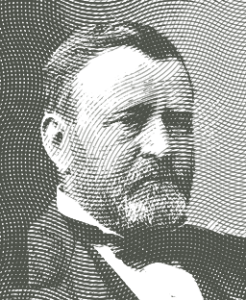

In 1892, seven years after your death, the historical medallion here was created. It depicted Washington's profile on the left called "Father", Lincoln's profile in the middle called "Saviour", and your profile on the right called "Defender". A very fitting medallion. I wish I had one.

Many today think of you primarily as the successful Union general in the Civil War. Well, in the middle of the 20th Century, there emerged another successful leader named General Dwight D Eisenhower who, like you, graduated from West Point, commanded the entire American army in a critical war, and later served 8 years as President of the United States.

Near the end of his life, he said this of you: "Grant devised a strategy to end the war. He alone had the determination, foresight, and wisdom to do it. It was lucky that President Lincoln didn’t interfere or attempt to control Grant’s strategic line of thinking... Grant is very undervalued today, which is a shame, because he was one of the greatest American generals, if not the greatest... Grant captured three armies intact, moved and coordinated his forces in a way that baffles military logic yet succeeded and he concluded the war one year after being entrusted with that aim. I’d say that was one hell of a piece of soldiering extending over a period of four years.”

From my perspective, though, being one of America's greatest generals, even the Defender of the Union in its most perilous crisis, does not automatically make you one of the greatest Americans in our history. For the United States has been blessed with great generals. But for the title of greatest Americans, there is a higher criterion. In my view, the title requires not only a whole lifetime of exploits, but extraordinary character - evidenced by love of country, honesty, humility, personal virtue, and moral courage.

With this standard, Mr. Grant, you belong to the American trinity with Mr. Washington and Mr. Lincoln.

I thought it would be delightful to compare the three of you in a number of areas.

First and foremost, character. The pinnacle of Washington's character was when he stepped away from power after the Revolutionary War, and then again after two terms as our first President. All Europe was shocked, shocked that Mr. Washington willingly gave up power.

Likewise, Lincoln's character represented the best American virtues of freedom for all, republican government, and equality before the law in every man's right to enjoy the fruit of his labor. You believed that it was Lincoln's "gentle firmness in carrying out his own will without apparent force or friction that formed the basis of his character". I think you even referred to Lincoln as "the most beautiful human being I have ever known".

And for you, all who got to know you became impressed with your kindness, gentleness, concern for others, and humility. From foot soldiers to fellow officers to opposing officers to citizens of foreign countries to the general American on the street. They were impressed. Likewise, for me, your humanity and personal qualities captivated me.

Second, the physical. Washington was tall at 6'2", and he was one of the best horsemen of his day, and yet also a graceful dancer and popular with the ladies on the dance floor. Lincoln was even taller at 6'4", the tallest US president ever. Though lanky and awkward in appearance, he was strong, having won wrestling matches in his younger days and became legendary for splitting the rails of railroad tracks with an ax.

You were considered short at 5'8", which happens to be my height. You did not dance, but you were Washington's equal with horses -- and I would dare say, even his superior for the stories I read about the way you handled horses, and how you trusted horses, and they returned the trust.

Regarding slavery, the three of you were, from one pespective, somewhat on the same page. While Washington did grow up in a slavery society and owned slaves himself like his ancestors and his Virginia neighbors, he did free his slaves in his will when he died. If all men of the South followed his example, American slavery would have died out like the Founding Fathers wanted in a couple of generations, and we would not have had a Civil War. Of course, all the world knows what Lincoln did with respect to slavery – he emancipated them in 1863. It was the cause against slavery that brought Lincoln to the White House. In your case, you came from an anti-slavery family, but married into a pro-slavery family, so you had to deal with that tension, even to the point of your own parents boycotting your 1848 wedding because of the slavery issue. When you inherited a slave from your father-in-law, you immediately gave him his freedom.

Regarding experiencing the world, what a huge difference! You were the most continental, living both in the East, the West, the Midwest, and serving in the war in Mexico. And you were the most traveled worldwide. I loved reading about how you returned to Mexico to help build up that nation, and then your 2-1/2 year odyssey around the world after your presidency -- to Europe, the Middle East, Africa, and Asia. In stark contrast, Lincoln never got to California, though he wanted to, and he had plans to visit Europe and Jerusalem, but never got that chance. And the farthest west Washington traveled was probably Ohio, and he only left America once for Barbados in the Caribbean.

For a moment, I thought about journeying down the path of your respective spiritual faiths, but maybe I'll save that topic for a future letter.

Instead, I'd like to explore one last comparison before concluding this letter. And that is perhaps the greatest sign of the affection you three had from your fellow Americans -- your funerals. Each was so different and unique!

Washington died in retirement at his Mt. Vernon home; four days later, a funeral procession took place at Mt. Vernon, overlooking the Potomac River, down to the tomb where the funeral service was held. People from the surrounding area attended his funeral. I myself visited Washington's tomb at Mt. Vernon several years ago.

But Washington died before the advent of the telegraph, and Congress was still meeting in session in far away Philadelphia. They did not learn of Washington's death until the actual day of the funeral. So eight days after Washington's funeral, another service was held in Philadelphia before Congress and other national dignitaries, where General Richard Henry Lee gave a formal funeral address in which he famously honored Washington as “First in War, First in Peace, First in the hearts of His Countrymen."

Lincoln's funeral was a personal affair as you took charge of the difficult arrangements. On that April 19th of 1865 in the East Room of the White House, you were seen standing alone next to Lincoln's casket, with tears streaming down your cheeks. You probably agonized then, and maybe for the rest of your life, about the question of what would have happened if you and Julia had accepted the invitation to join them that evening in the President's box at Ford's Theater. Could you have prevented your friend's assassination?

What painful and awful days those must have been. And then for the millions of Americans who gathered at the railroad tracks to observe Lincoln's funeral train on its journey from Washington, DC to Springfield, Illinois -- a journey that retraced his route to Washington in 1861. Lincoln’s casket was removed from the train in ten cities so that mourners could participate in memorial services and venerate him. Lincoln's train finally reached its destination, and Lincoln’s body was placed in its permanent tomb. Several years ago, I myself went on a pilgrimage to that tomb in Springfield.

And what of your own funeral 20 years later in 1885? As you wished, your funeral was held in New York City, your adopted home in your last season of life on earth. It was a sight to behold – your casket being drawn by two dozen black stallions in a 7-mile procession of mourners, ambling up and down the streets of New York City. To their final destination – Grant's Tomb in Riverside Park, just four miles from your home. Your pallbearers included your two closest Union generals, Sherman and Sheridan, and two Confederate generals, Buckner and Johnston.

Over 1.5 million Americans attended your funeral, including President Grover Cleveland, two former US presidents, the justices of the Supreme Court, and other dignitaries. You were eulogized in services and newspapers all over the land, many likening you to George Washington and Abraham Lincoln.

As I close this letter, I want to tell you that there was one special anecdote I learned from your biography which wasn't apparent in your memoirs. The story behind your memoirs. And I don't mean how Mark Twain became your publisher or your battle with throat cancer or the money you needed to earn for your family. No, it was that basic, honest question you asked yourself – can I really write a book that people will want to read? For after all, you were not a writer – you were a general, expert horseman, unsuccessful farmer, shopkeeper clerk, loving husband and father, and oh yes, President of the United States. So it was a fitting question of whether you could write so late in life. I must say, though, it certainly seems providential to have had Mark Twain as a friend and encourager.

And your question is my question. After an extensive career as a finance executive in several nonprofit organizations, can I write things that people will want to read? Can a "numbers guy" like me be adept with words?

In this, I am reminded of one of my favorite stories from a time when I lived in the beautiful Pacific Northwest. My family had picked up the recreational sport of snow skiing. You may have read about skiing, which became a sport in Europe starting in the 19th century.

Anyway, one winter day, I had just finished a fun-filled day of skiing with my 9-year-old son and 5-year-old daughter. As we trudged back to our vehicle after a full and tiring day, my daughter talked and talked and talked – about her favorite ski runs, about when we would go skiing again, about what she’ll do when we get home, and a myriad of other things, you know, rambling things. As we sat down in our vehicle for the one-hour journey back home, I casually remarked to my son, “Your sister sure likes to talk, huh?” And he chuckled, “Yeah, she does!” And then my 5-year-old daughter uttered her classic, never-to-be-forgotten words, which to this day, always brings a smile to my face: "No Daddy, it's not that I like to talk... it's that I have a lot to say!"

And that captures how I feel about these Letters of mine. It's not that I like to write... it's that I have a lot to say.

Mr. Grant, you are one of a handful I call Friends of the Ages to whom I am writing. Mr. Lincoln is one of these. One is a favorite Founding Father. And two lived in the 20th Century.

Your race to finish your memoirs before you died is a poignant reminder for me -- that our God may give me, perhaps, only one more decade of life to write all of the Letters that are inside of me, striving to emerge.

I hope I can write many Letters to you before I meet you, and your dear Julia, in heaven.

Until my next Letter,

Ted at Common Reason

Comments